They are works on Hegel, Nietzsche, Mallarmé, Marcel Duchamp, Darwinism, Pyrrho... My ‘hidden’ works may be very different from my ‘public’ works, and I hope one day to be freed from this ‘double identity’ – this gap between what I do and what people think I do.

Version française disponible ici.

The recent publication of a paper on Hegel by Meillassoux awoke an already 10 years old insight of mine regarding his way of practicing the history of philosophy and what it could make us suspect - mark my word - regarding his own philosophical work. Let me share here a first version of the idea, and please share your thoughts on it.

I believe the key to the whole thing was given in the Mallarmé studies Meillassoux undertook in the early 2010s (of whom The Number and the Siren only scratches the surface, but gives just enough to deliver the key). Later, Meillassoux gave maybe the clearest model of the phenomenon I’m aiming at, in his interpretation of Nietzsche - given in classes I was lucky to attend. Finally, the tendency seems to be confirmed in the recent - and hilarious - conceptual apparatus Meillassoux elaborated regarding Hegelian contingency.

Let me try and directly establish the parallel between these three cases. I hope it will make clear what is meant, in the subtitle of this post, by “paranoid historiography”, and why this historiographical mode might not only refer to the one Meillassoux practices, but also to the one he encourages us to practice on his own work.

I must immediately specify that I do NOT intend to disqualify his work by calling it “paranoid”. As far as I am concerned, Meillassoux’s work on the history of philosophy is nothing short of extraordinary.

“Hegel, Nietzsche, Mallarmé”

What is this parallel? First, in all three cases - Hegel, Nietzsche, Mallarmé - Meillassoux’s reading is unique in that it hinges on the historical hypothesis of a secret (or at least something not told), that is an integral determinant of the nature and content of those authors’s published works.

In the case of Hegel, the secret is independently known and recognized by other historians: it concerns Hegel’s positions (of rejection) regarding some religious dogma, in particular the survival of the individual soul after the death of the body. Hegel’s silence on the matter is finely orchestrated, and efficiently restituted by Meillassoux who - as he usually does - gets his information from personal correspondence as well as from the finest dialectical passages of the Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion1. Because of this secret, some important elements of the Hegelian system go unmentioned in his official work (a situation generally understood as a necessary action to avoid censorship and persecution by the State).

In Nietzsche’s case, the secret is more dispersed and inherent to the whole Nietzschean mode of discourse. It can be found in examining together his early works on language, his approach to religions’ founding (for example the founding of Islam by Muhammad), and the content of his mature works including and especially the posthumous fragments (and the difference between the published and the unpublished works). The secret concerns the very status of Nietzsche’s last published works, and the fact that he acts as a religious founder addressing a modern, nihilistic and skeptical audience. The religious founder, according to Nietzsche, knows, but does not tell, that they must convince themself of the truth of what they are saying (they are their own first convert). They know that Truth does not really come to them from the Heavens, and that they are responsible for it - but they have to pretend otherwise and to convince themself otherwise. Nietzsche, in this interpretation, must have formulated more or less consciously such an authorial project, but could not have inscribed it in the text of the work (since it is a secret), though it is indeed what determines the content of his last published works.

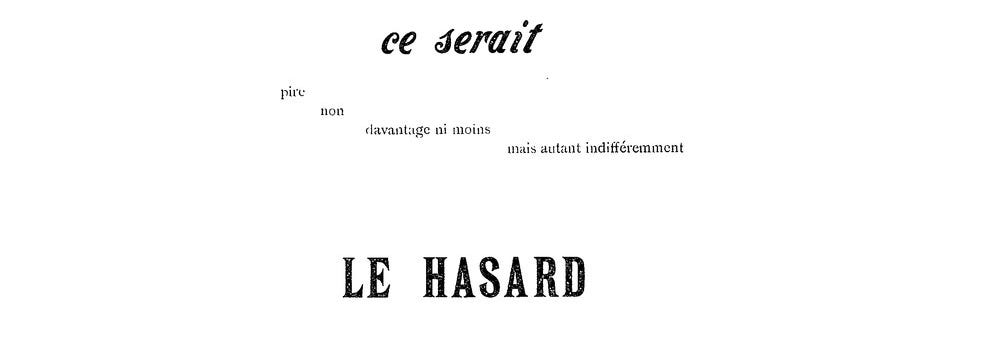

In Mallarmé’s case, the secret is really deserving of the name: something barely hinted at anywhere, and that Meillassoux has to himself discover and grandiosely reveal. It is, as we know, that some of Mallarmé’s late masterpieces (“Salut”, “À la nue accablante tu” and especially, of course, “Un coup de dès jamais n’abolira le hasard”) are hiding a cipher, a system of numerical coding that gives an added meaning to the work and impose a poetic constraint on the number of words in those poems.

There is more. Not only a secret is historically important in producing the works as they stand, but this secret, or the facts and circumstances of it, directly play a role in the philosophical interpretation we must give of these works, and this in a very peculiar way. In all three cases, the existence of the secret regarding the context of production and publication must change our interpretation, and make the latter neither internalist not exactly externalist. Our interpretation must in fact rest on the consideration of an interference of the speech-act in its singularity on the content of speech itself, that cannot simply be read as it is.

It is useful here to remember Meillassoux’s fascination (which I share) for the idea of the “pragmatic contradiction”, and its use in producing a non-deductive refutation, already in Aristotle but especially in Fichte as read by Isabelle Thomas-Fogiel. A pragmatic contradiction is a way for a discourse to be self-refuting, not at the pure internal level of its content (as for ordinary contradiction), nor at the external level (because reality disagrees with it), but because its content is contradicted by, incompatible with, the very act of speech that affirms it2. To be clear, Meillassoux does not exactly find a pragmatic contradiction in the authors I am here considering (in fact his interpretations are far weirder), but the domain is the same : it is the domain of interference or retroaction of the speech-act itself on the content of speech.

Hegel’s case is remarkable. The general idea is that Hegel’s system has the peculiarity of deducing its own existence as an historical event. Because the Spirit, being speculatively deducted, has the propriety of realizing itself in its other, and to actually exist, finding its absolute expression in actual philosophy, the concrete existence of the Hegelian system is, so to say, a pragmatic component of what is stated by Hegel’s discourse. We see therefore that Hegel already operates in general at the level of the perturbance or interference between the speech-act and the content of speech, a fact that must rightly fascinate Meillassoux. The question his paper asks is: what happens if an essential part of the speculative content is not stated in the system as published by Hegel ? The situation is, as we said, that the Prussian constitutional monarchy makes it so that the Absolute Spirit, at the moment of its ultimate expression in philosophical actuality, omits to state the truth regarding the finitude of the individual soul and the absence of physical resurrection of Christ. At this point, Meillassoux argues, the System is contradicted by factuality. Hegel cannot be right in what he says, if he omits to say something essential, because his system implies that his work is the expression of the Absolute, that happens in a specific realization of the political sphere also embodying the Spirit. Concrete censorship by the State, manifested in Hegel’s secret, contradicts the content of Hegel’s system by refuting that the State is the realization of the Spirit and therefore, also, Hegel’s philosophy.

In Nietzsche, as we said, we have the discourse of a founder of religion, who cannot actually provide a rational foundation for truth, but imposes it by their force of expression and conviction, to themself in the first place. What is however fascinating, in Nietzsche’s case, is that the “revealed” content itself includes the idea that rational argument is an attempt by a Will to Power to impose themself, that truth is a fundamentally interested category, that must be suspected, etc. For it is from Nietzsche’s own work that the suspicion of a secret regarding the nature of his discourse can be elaborated by Meillassoux. Another way of stating the same thing, is to say that we are lead to suspect Nietzsche because he is a founder of religion, but that this kind of suspicious lookout is precisely the kind of thing that his “religious” revelation wants to provoke, precisely the conversion Nietzsche wants. This is why Nietzsche is unique and so seductive in the history of philosophy, and why Meillassoux, in the end, is interested: Nietzsche is maximally seducing when he gives the very weapon that leads to relativize his own discourse, which, in doing that, reinforces it. This is precisely what it means, according to Meillassoux, to be a founder of religion for a modern skeptical nihilistic audience.

In Mallarmé, the point is more contained, but no less fascinating. According to Meillassoux, not only has Mallarmé inserted a secret in his work, but the way this secret operates makes it so that the very expression of content in the poems becomes uncertain. According the Meillassoux, the very fact that the secret cannot be proven to be there, that it is impossible to rigorously attest that there is a code, is an integral part of Mallarmé’s speech intent. Indeed, the text of “Un coup de dés…” contains a literal “PEUT-ÊTRE”, “MAY-BE”, that, for complicated syntaxical reasons, carries the indetermination of the presence or absence of a secret code in the poem. The meaning of Mallarmé’s poem are of course notoriously mysterious, but according to Meillassoux the key to their meaning must include the hypothesis of a secret that determinates them.

Let us go one step further. In all three cases, the speech act, determined by the secret, produces a strange form of contradiction, a dialectical real contradiction (generally ignored by the historiography for a simpler, unilateral reading), an undecidabilty or necessary instability of interpretation. We would do well to remember here what Meillassoux said to Graham Harman in an interview, regarding his youthful fascination for such “heterodox dialecticians” as Kojève, Feuerbach and Debord3. Evidently, this fascination for heterodox dialectics is not only of his youth, and remains a enduring trait of his way of doing history. We partially explained already how this dialectical contradiction emerges in each case:

The Hegelian speech is contradicted because it entails theses (on the mortality of the soul) which, by not being stated, contradict the very status of the System. The dialectics here is not the Hegelian one, that is precisely the point that Meillassoux wants to make ! Traditional historians have ignored this contradiction and this tension internal to the System, by reintroducing these theses at their place in the system, and/or explaining Hegel’s silence by psychological and social facts external to the system.

The Nietzschean speech - that is well known - cannot be considered as propositional, nor as non-propositional. As Meillassoux states it, if one thinks that Nietzsche is trying to state true things, the position is contradicted by his challenge to the notion of truth. Inversely, if he is not trying to state true things, then what is he doing? What truth status can the statements of an author that challenges the notion of truth have? One option is indeed to not take him seriously at all. Another is to choose the critique of truth, and to make him a fundamentally ironic, detached author (but then, how can we account for the seriousness and intensity of such revelations as the Eternal Return?). A third option is to choose the content revealed, the Eternal Return and the Will to Power (but then, how to account for the relevance and strength of his critique of truth?). In reality, this instability is precisely what it is to be Nietzschean : to naively state ones suspicions, to blindly engage in lucid critique. As Meillassoux told us in his class, he endeavored to make a course on Nietzsche when he finally found “a way to say something that was not less interesting than what Nietzsche himself is saying”, that is, a way to pierce the secret of the enigmatic status of his affirmations. Traditional historians, as we said, will tend to ignore this dialectics by choosing either truth or non-truth.

Mallarmé’s speech also engages us in a kind of absurd dialectics, that Meillassoux delights in expanding. Because of the structure of the secret, Meillassoux’s interpretative hypothesis can only be convincing if it is not quite convincing. Meillassoux asks of his reader that they doubt of his arguments’ strength, for only then can they really have strength. (One is here reminded of Meillassoux’s fascination (did he talk about it about Nietzsche?) for the idea of a contradictory order given by libertarian or hippie parents to their children : “disobey”).

We know from his teachings on Mallarmé that Meillassoux takes very seriously the importance and the inopportunity of the act of publication. He seems to have inherited from Mallarmé a politics of retreat and non-publication. His interest goes beyond the question of the politics of texts, however, and it evidently takes on a directly philosophical dimension for him. As he shows in his historiography, the act of publication has philosophical consequences, might produce effects on the very nature or content of one’s system, in a way he is fascinated by.

And others…

Can we go explore these ideas beyond these three authors? It is clear that Meillassoux has a general tendency to go look for something to contradict or make fail or drive into a corner the main philosophy of an author, in details or non-explicit statements or affirmations only present in almost private correspondence. More generally, he likes to consider philosophical systems at a level that, as I said, is neither internal nor quite external. As the generation immediately after him saw and described, Kant contradicts his very position by stating things about the transcendental, with a way of knowing he does not grant himself. Husserl, shows Meillassoux, is forced to assume the ancestral existence of a large worldly spirit, in order for his own version of the transcendental to apply in the world (that is Husserl’s answer to the problem of ancestrality), as he himself admits eventually. If Meillassoux is interested in Montaigne, it is because he takes to the point of insurmountable tension the fact of being at the same time a devout catholic and a strange form of atheistic relativist, rendering indecipherable the status of his affirmations. In Descartes, Meillassoux is interested in the way the free creation of eternal truths (only stated in correspondence) overdetermines the system, to the point of making it unstable - which takes us in a strange heterodox dialectics of hyper contingency (something that Guéroult, for example, tries to discipline in his interpretation). One could probably go on…

Maybe all of this works, maybe not. But we might want to look in particular in what has not been revealed to the public yet. In the end of this same interview by Harman, Meillassoux states that :

“I think no one can imagine the number of works I have in progress, or their frequent incongruity with respect to what is commonly viewed as the center of my interests. They are works on Hegel, Nietzsche, Mallarmé, Marcel Duchamp, Darwinism, Pyrrho... My ‘hidden’ works may be very different from my ‘public’ works, and I hope one day to be freed from this ‘double identity’ – this gap between what I do and what people think I do.”

Note that Hegel, Nietzsche, Mallarmé are precisely the authors here considered. And while it might be supposed that his work on Darwinism belongs rather straightly with his works on finality, what of Duchamp? (who famously transformed the world of art by promoting non-art to artistic status in a weird performative joke) what of Pyrrho?(who stated that anything, as well of its contrary, was the case, in a sort of lived contradiction) In both cases, I believe we remain very close to the kind of heterodox dialectics that I have been suggesting. Let us see what the future holds.

Deadpan comedy

Any person lucky enough to have been taught in person by Meillassoux must have been struck, as well as by anything else, by a kind of vibe : the vibe of deadpan comedy. Meillassoux is, indeed, very funny, but never laughs. His classes are often constructed towards a perfect, deeply evocative joke, but, a dry smile on his lisps, he lets the audience decide.

In the history of philosophy as practiced by Meillassoux, there is immense joy, evident pleasure in divulging the secrets of authors, and sometimes to refute them by the weirdest sorts of pragmatic contradictions. The paper on Hegel, by its very thesis, is extremely funny. But Meillassoux does not laugh. In a way, he remains very serious.

Should we go further still? Are we invited by Meillassoux to suspect more? Should we suspect that he himself, in his politics of publication and the content of his text, plays the same kind of double-dealing he perceives in others?

How much should our suspicion run wild? Should we think there is, as he said in the interview, something “hidden” in his works, a “double identity”, a “gap between what he does and what people think he does”? And what should we suspect? The very thesis of the necessity of contingency, obtained through an hilarious dialectics of correlationism in After Finitude ? The idea of the God-to-come, this strange contradiction of a hope that cannot by definition be supported by something in reality, and that, in a way reminiscent of Hegel, is brought to the world by the very publication of Meillassoux’s works? Should we suspect the material inexistence of The divine inexistence, its status of perpetual limbo, existing only in non-official copies circulating among his fans?

Or maybe nothing should be suspected. Maybe Meillassoux is a paranoid historian, but an entirely serious author, to consider with a straight face and a lot of good sense. In any case, he surely will not let us have a way to irrefutably reveal his secrets. That would certainly spoil the entire thing.

Incidentally, this is another characteristic trait of Meillassoux’s paranoid approach: the tendency to base interpretation on the association of marginal, external or personal elements about an author, with the very heart of their philosophical work.

According to Aristotle (as paraphrased by me), stating the reality of contradiction is a pragmatic contradiction, because the possibility for the negation of what is true to be also true is contradictory with the very essence of affirmation. That is, in a modern vocabulary, the propositional attitude itself always implies non-contradiction. Another example of pragmatic contradiction would be the one described in Moore’s “paradox”: the impossibility to rationaly state a sentence like “It is raining but I do not believe so”. The sentence is contradictory, not in its pure content (since I can say without contradiction, about somebody else “ It is raining but they do not believe so”), but contradictory with the very fact of being stated.

Quentin Meillassoux, Philosophy in the Making (2011), p. 173:

“In the first years of my studies, the books that gave me the most violent feelings and the purest enthusiasms were all works by heterodox dialecticians. I was bewitched by three authors in particular: Feuerbach in The Essence of Christianity, Kojève in Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, and Guy Debord. I was a passionate reader of the Situationists (having co-founded in my youth a journal called Delenda that was entirely devoted to their standpoint and lasted for two issues). I endlessly read and re-read the three major works of Debord: The Society of the Spectacle, Comments on The Society of the Spectacle, and Panegyric.”